Variations: Dinanabolele, Linanabolele (pl.)

Thakáne and her two brothers were the children of a Basotho chief. In some versions there is only one brother, Masilo; in some retellings the siblings are orphans, in others their parents are merely distant figures. Either way Thakáne was like a mother to her brothers. She cared for them, made their food, and filled their water jugs. When they had to go to school, it was Thakáne who took them there. When they were circumcised in the traditional grass huts, the mophato, it was Thakáne who took them there and waited on them until the ritual was over and they had rested. It was their sister who brought them the clothes they would wear as men.

But Thakáne’s brothers did not accept her choice of clothing. Only items made from the skin of a Nanabolele would do. They wanted shields of nanabolele hide, and shoes of nanabolele leather, and clothing of nanabolele skin, and hats cut from nanabolele, and spears tied up with strips of nanabolele. They refused to leave the mophato until their request was fulfilled.

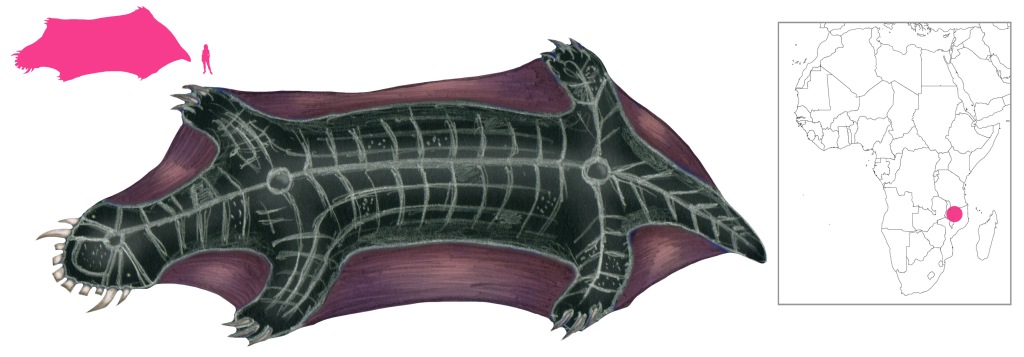

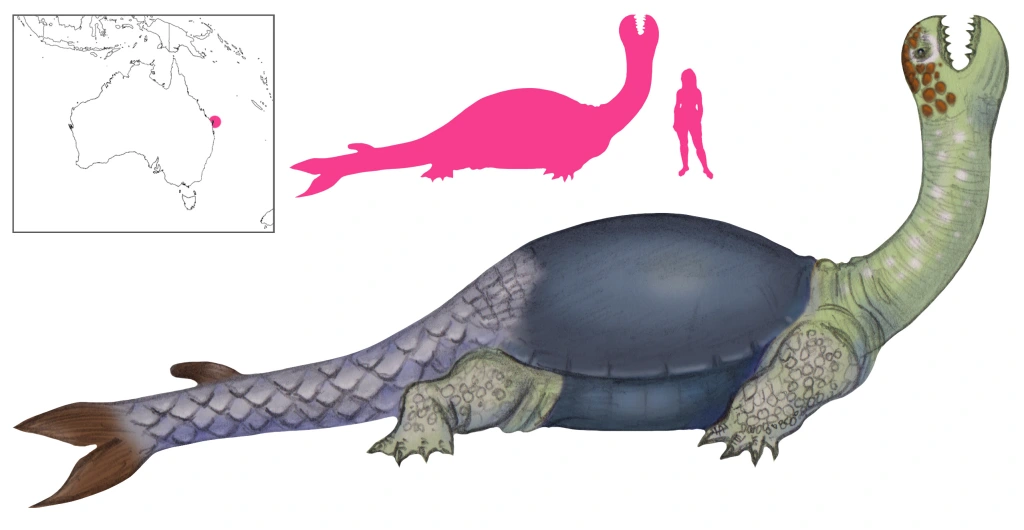

It was a tall order. The nanaboleles, they who shine in the night, were horrid, reptilian, dragon-like creatures that live underwater and underground. They glow in the darkness, giving off light like the moon and stars do. They were deadly predators. Surely there was some mistake! “Why do you ask the impossible?” asked Thakáne. “Where am I supposed to find nanabolele skin? Where? Ná?” But her brothers would not be swayed, declaring that it became them, as the sons of a chief, to wear nanabolele skins.

So Thakáne set out, knowing that if their father was around, he would have done the same. It fell upon her to accomplish the task in his stead. She set off with oxen, beer calabashes, sweetcorn balls, and a large retinue in search of the nanaboleles. She sang as she went:

“Nanabolele, nanabolele!

My brothers won’t leave the mophato, nanabolele!

They want shields of nanabolele, nanabolele!

And shoes they want of nanabolele, nanabolele!

And clothes they want of nanabolele, nanabolele!

And hats they want of nanabolele, nanabolele!

And spears they want of nanabolele, nanabolele!”

When Thakáne sang, the waters of the nearby stream parted, and a little frog hopped out. “Kuruu! Keep going!” it told her. Thakáne kept going from river to river, following the directions given by frog after frog, until at last she came upon the widest and deepest river yet. She sang her song, but nothing responded. Then she tossed some meat in, followed by an entire pack ox, but nothing happened.

Finally, the waters stirred, and an old woman stepped out, greeting Thakáne and inviting her to come in with her. Thakáne followed the old woman into the river, followed by her company. To her surprise, there was an entire river under the water, dry and breathable. But there was nobody there. It was empty and silent as the grave.

“Where are all the people, Grandmother?” said Thakáne to her guide. “Alas”, said the old woman. “The nanaboleles have eaten them, adults, children, cattle, sheep, dogs, chickens, everything! Only I was allowed to live, I am too old and tough to eat, so they make me do their work for them”. “Yo wheh!” said Thakáne. “We are truly in danger then”. But the old woman bade them hide, leading them into a deep hole which she covered with reeds.

It wasn’t long after Thakáne and her friends had hidden that the nanabolele returned to the village, sounding like a huge herd of oxen. The dragons glowed, shining like the moon and the stars, but they did not sleep, instead sniffing around intently. “We smell people!” they snarled. But they found nothing, and eventually tired and went to sleep.

That was the opportunity Thakáne had been waiting for. She and her companions emerged from hiding and, singling out the biggest nanabolele, quickly slaughtered it before it could wake up the others. Then they flayed it in silence and prepared to leave.

Before they left, the old woman gave Thakáne a pebble. “The nanabolele will follow you. When you see a red dust cloud against the sky, that will be them on your trail. This pebble will save you from them…”

Sure enough, dawn had barely broken when Thakáne saw the cloud of red dust. The dragons were in pursuit! Thakáne quickly dropped the pebble on the ground, and it grew, becoming an enormous mountain that she and her friends climbed. They took refuge at the top, while the nanaboleles exhausted themselves trying to climb it. Then, as the reptiles lay catching their breath, the mountain shrank, Thakáne picked up the pebble, and the chase continued.

Thus it went on for several days, with the nanaboleles catching up only to be worn out by the pebble-mountain. But when Thakáne reached her home, she called upon all the dogs of the village to attack the nanaboleles. The creatures, terrified, turned tail and ran back to their abandoned village under the river.

There was only one thing left to do. The nanabolele skin which gives off light in the dark was cut and prepared into items of clothing and armor and weapons, and Thakáne herself took them to her brothers in the mophato.

Nobody else had seen such wondrous items, and Thakáne’s brothers rewarded her handsomely, giving her a hundred head of cattle.

References

Dorson, R. M. (1972) African Folklore. Anchor Books, Doubleday & Company, New York.

Jacottet, E. (1908) The Treasury of Ba-Suto Lore. Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., London.

Postma, M. (1974) Tales from the Basotho. University of Texas Press, Austin.