Variations: Vodianoi, Vodyanik, Vodnik, Vodeni Moz, Deduska Vodyanoy (Water-Grandfather), Vodianoi-chert (Water Devil), Vodianikha (female), Topielec (Drowner, Polish), Vodyany-ye (pl.); Bolotnyi (potentially)

![Vodyanoi]()

The malevolent and murderous Vodyanoi, from voda or “water”, is the Slavic water spirit. It frequents lakes, ponds, rivers, and other bodies of water, but it especially prefers mill-ponds. Their homes range from the humble dwellings of sand and slimy logs of Olonets to underwater palaces of crystal, decorated with gold and silver taken from shipwrecks, and illuminated by a magic stone shining brighter than the sun. The palaces are primarily known from Kaluga, Orel, Riazan, and Tula. The female vodyanyoi is also known as the vodianikha, although a rusalka or a drowned woman will also be taken as a bride. Variants of the vodyanoi are known in Belarus, Poland, and Yugoslavia.

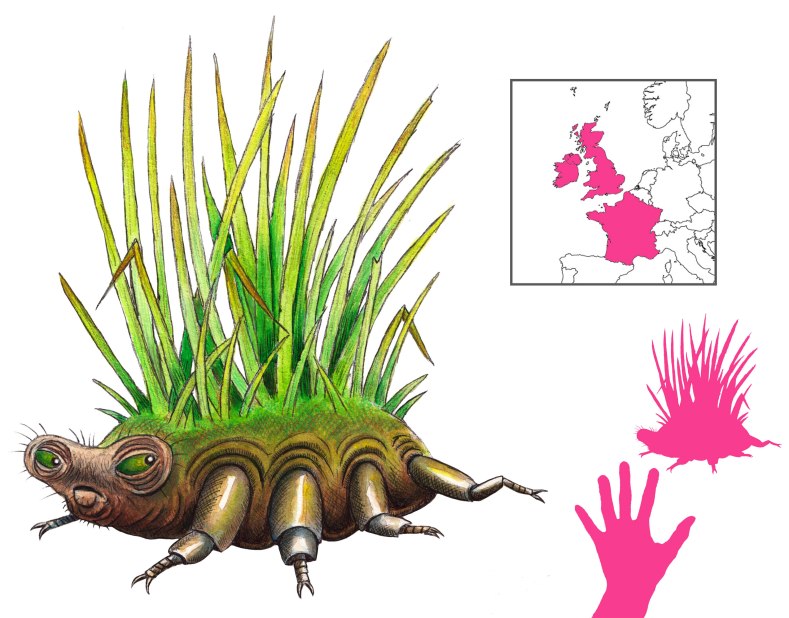

A vodyanoi varies wildly in appearance. It can be roughly human in appearance, with big paws, horns, tail, and eyes like burning coals; it can be a huge man covered with grass and moss, with shaggy white fur, or with scales; it can be black with huge red eyes and a long nose, or bluish and slimy, bloated and crowned with reeds. Sometimes it appears in the form of a human, as an old man with green hair and beard that turned white with the waning moon, as a white-bearded peasant in a red shirt, as a naked woman with enormous breasts combing her dripping hair while seated on a log, or in the form of guardsmen and children. It can be half fish and half human, or appear as a huge moss-covered fish, a swan, or even a bouquet of red flowers on the water. In Smolensk the vodyanoi is humpbacked and has the feet and tail of a cow, while in Vologda it is a log with little wings flying over the water. A vodyanoi out of the water and in human guise can be identified by the water oozing out of its coat.

The vodyany-ye are immortal, but grow younger or older with the moon. They are weak on land, but virtually invincible in the water, and they dislike going out of the water beyond the bank or mill-wheel; some vodyany-ye refuse to emerge from water beyond the waist. They like to ride livestock until they die of exhaustion. Their presence in the market is an omen; if a vodyanoi buys corn at high prices, the harvest will fail, but a vodyanoi buying cheaply foretells bountiful crops.

They rest in their palaces during the day, and come out in the evening splashing the water with their paws, making a noise that can be heard over great distances. Vodyany-ye hate humans and lurk in the water after sunset, dragging people in when the opportunity arises. Those they drown become their slaves, or if attractive enough their wives. They take offense to anyone attempting to retrieve the bodies of the drowned, seeing them as their rightful property. Recovered bodies with bruises and marks on them were seen as bearing the scars of battle with a vodyanoi. In some places the presence of a vodyanoi became a serious threat. One mill-pond in Olonets held a vodyanoi family that required a constant source of corpses to eat. The inhabitants of the area learned to avoid the pond, and the family was eventually forced to relocate.

A vodyanoi sees mill-dams as an insult, and will destroy them to keep the water flowing. Horses smeared with honey, hobbled, and drowned with millstones make good placatory offerings. Drunk passers-by can also be pushed into mill-ponds to earn the vodyanoi’s trust.

As with other evil spirits, a vodyanoi can be exorcised; in fact, in some areas such as Tula, the vodyanoi is indistinguishable from the devil. Shooting a vodyanoi with buttons has been known to kill them as well. But while a vodyanoi can bear grudges, it can just as soon show gratitude. One vodyanoi who was aided in fighting off a rival promised never to drown anyone.

A vodyanoi is not hostile to fishermen and millers due to their affinity with water. Millers would deposit bread, salt, vodka, black sows, and ram’s heads at the water’s edge as offerings to the vodyanoi, and offer black roosters when building a new mill. Some millers were on such good terms with their local vodyanoi that they dined with them every night. Fishermen, on the other hand, would toss butter or tobacco into the water, saying “here’s some tobacco for you, vodyanoi, give me a fish!” A pleased vodyanoi would drive fish into a fisherman’s net. Finally, beekeepers also kept up good relations with the vodyanoi by offering honey and wax, and in return the water-spirit prevented humidity from damaging the hives.

The bolotnyi, from boloto or “swamp”, is a possible variation of the vodyanoi found in swamps.

References

Aldington, R. and Ames, D. trans.; Guirand, F. (1972) New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Paul Hamlyn, London.

Dubois, P.; Sabatier, C.; and Sabatier, R. (1992) La Grande Encyclopédie des Lutins. Hoëbeke, Paris.

Ivanits, L. J. (1989) Russian Folk Belief. M. E. Sharpe, Inc., Armonk, New York.

MacCulloch, J. A. and Machal, J. (1918) The Mythology of All Races v. III: Celtic and Slavic. Marshall Jones Company, Boston.

![]()

![]()

Dear Alex S.,

Dear Alex S.,