Variations: Muscardin; Dormouse; Musquelibet, Musquelibus, Musquilibet (possibly)

![Muscaliet]()

Nobody is quite sure what a Muscaliet is. Our only source for this unusual rodent is found in the bestiary of Pierre de Beauvais, and it appears to have been cobbled together from multiple unrelated accounts.

The muscaliet is found in India, in the land of the three talking trees that predicted the death of Alexander the Great. This by itself is suspect, as the accounts of Alexander in India only mention two trees, consecrated to the sun and moon. Then again, the sun-tree was said to have spoken twice and the moon-tree once, making for three tree speeches. The life of a copyist was a thankless one.

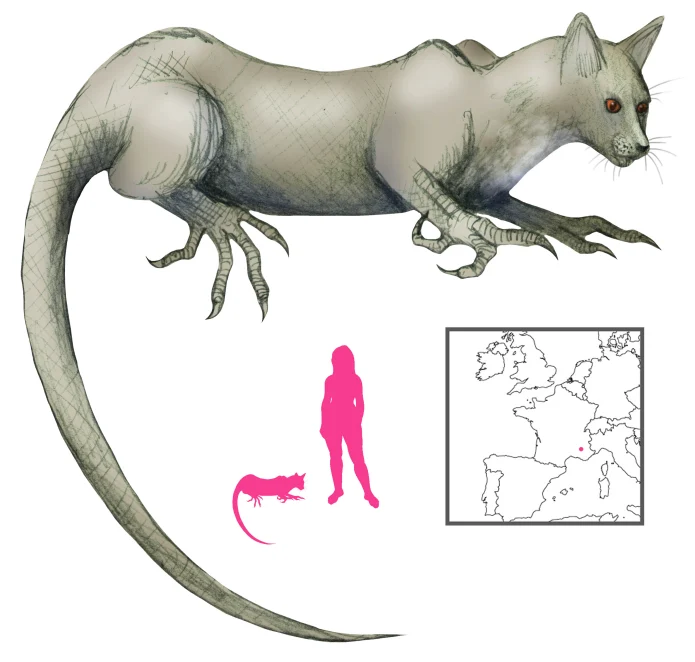

Beauvais gives the muscaliet a body like a hare, but smaller. Its legs, feet, and tail are like those of a squirrel, but the tail, while held in a squirrel-like manner, is larger. It uses the strength in its tail to jump from tree to tree. Its head is rounded, its ears small and weasel-like, and its nose long and pointed like a mole. There is a tooth sticking out of its mouth on either side, like a boar’s tusks, and it has bristles around its snout like the bristles on a boar’s back.

A muscaliet is a highly adept climber. No animal can catch it in the trees, and its claws are so sharp that it can cling to any surface. It eats fruits, leaves, and flowers and digs out its dens in the roots of trees. It is so “hot by nature” (calde de nature) that the tree it lives in eventually rots, withers, and dies as the muscaliet gnaws away at the roots.

This is a moral lesson. The tree represents a human; its leaves and flowers are good deeds, and its fruits are the soul. But the muscaliet is Pride, its sharp teeth are cutting words that Cruelty brings, and its feet show that cruelty is tenacious. Once Pride takes up residence within us, Beauvais warns, it rots us from the inside out.

The term “muscaliet” itself is an archaic French term for the common dormouse or muscardin (Muscardinus), that which Buffon described as “the least ugly of all the rats”. Its name is derived from its presumed musky odor; whether this attribution came before or after Beauvais’ usage is unclear. The –caliet part of the name superficially suggests heat, which would have inspired our bestiarist to describe it as “hot by nature”. Alternative, “muscaliet” may have been derived from the musquelibet, a creature like a roe deer in size, with an abscess-like growth that produces musk. This is the musk deer Moschus moschiferus, which does have tusks like a boar but little connection to the muscaliet otherwise – not even musk is mentioned.

Is this the fox-sized mouse described by Aristotle? It was a wonder of India found by Alexander, a mouse the size of a fox and with a noxious bite that harmed animals and humans. This sounds like a rat, and perhaps an early allusion to the diseases carried by those animals – rats were unknown to the ancient Greeks and Romans, with black rats appearing in late antiquity and brown rats showing up in the 16th century. Tales of rats with toxic bites combined with dormouse and musk-deer anecdotes are likely the basis for the tree-poisoning muscaliet, which exists as a moral warning and not a zoological account.

References

de Beauvais, P.; Baker, C. ed. (2010) Le Bestiaire. Honoré Champion, Paris.

Buffon, G. L. L. (1775) Oeuvres completes de M. le Cte. De Buffon, t. II. Imprimerie Royal, Paris.

Cahier, C. (1856) Bestiaires. Melanges d’Archeologie, 1856(IV), pp. 55-87.

de Cantimpré, T. (1280) Liber de natura rerum. Bibliothèque municipale de Valenciennes.

Cuba, J. (1539) Le iardin de santé. Philippe le Noir, Paris.

Godefroy, F. (1901) Lexique de l’Ancien Francais. H. Welter, Paris.

Kitchell, K. F. (2014) Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon.

Magnus, A. (1920) De Animalibus Libri XXVI. Aschendorffschen Verlagbuchhandlung, Münster.

Unknown. (1538) Ortus Sanitatis. Joannes de Cereto de Tridino.

de Xivrey, J. B. (1836) Traditions Tératologiques. L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris.